|

Hanna

Reitsch

(1912 - 1979)

WHILE THE "Right Stuff" men were still sitting behind

conventional engines and looking through the arcs of their propellers, a

pilot in Germany was routinely setting records in exotic jet- and

rocket-powered aircraft and helping draft the first blueprints for a

trip to Mars.

While the Allied air forces were pounding Germany's industrial

infrastructure to dust during World War II, Germany turned in

desperation to its best test pilot--arguably the most professional and

courageous who ever lived--to push aviation technology far beyond

anything the Allies ever dreamed of in a last-ditch effort to defeat

them.

When a powerful Russian army was only scant yards from Hitler's bunker,

a pilot in Germany landed a bullet-riddled plane (with a freshly wounded

comrade writhing in the cockpit) on a shell-cratered Berlin street in a

futile effort to rescue Hitler from the deadly trap. Shortly after, the

pilot successfully took off from the same street through a hailstorm of

Russian gunfire, again swerving around the shell craters.

Long after the war, when most would be in retirement, this pilot took

off from a field near State College, Pa., to try out a glider that

belonged to a friend. When the glider landed--after flying almost 600

miles without power--yet another stun-ning record had been added to

aviation history.

These are but a few of the incredible exploits of Hanna Reitsch.

The ascent of Reitsch's career and WWII German aviation, both began,

remarkably enough, with the restrictions imposed against the German air

force by the Treaty of Versailles. Few powered planes were permitted in

Germany after World War I. A loophole in the restrictions allowed

Germany to form dozens of glider clubs that attracted thousands of

fresh-faced, eager young pilots. The clever German militarists were

developing a large cadre of skilled pilots who would one day trade their

harmless little gliders for much more formidable craft marked with the

distinct "Balkenkreuzen" of the Luftwaffe.

In 1932, 20-year-old medical student Hanna Reitsch joined a glider club.

Soon, she set the first of at least 40 aviation records credited to her

and was one of the first glider pilots to cross the Alps.

Like many of her fellow glider pilots, Reitsch graduated to powered

aircraft when an emboldened Germany began rebuilding its air force in

earnest.

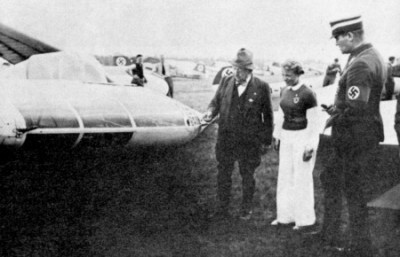

Hanna Reitsch and the Ho III a

Reitsch's talents were soon harnessed to help hone

the edge of the Luftwaffe, and she took on unimaginably dangerous jobs.

One type of plane she tested was a heavy bomber that had steel blades

installed on the leading edges of the wings to cut the heavy steel

cables used to tether barrage balloons. During one demonstration for

Luftwaffe brass of this hair-brained scheme, Reitsch made a graceful

landing and exited the cockpit smiling and waving after deliberately

flying into the cables. Only she knew that the wing had almost been

ripped from the plane when she hit a cable and she had to fight for her

life--second by unnerving second--to get the crippled plane on the

runway.

On another hair-raising flight in a stricken plane, instead of bailing

out, Reitsch calmly recorded flight data with paper and pencil because

she did not think she would live long enough to make the report in

person.

Many of the designs that Reitsch tested were novel and innovative, and

some were just simply ill-conceived deathtraps. Reitsch was the only

civilian and only woman to receive the Knight's Cross with Diamonds. Had

Reitsch never lived, a hypothetical screenplay of her adventures would

probably be dismissed as being "too far-fetched to be believable."

Hanna Reitsch demonstrating a prototype helicopter

The first operational jet fighter, the twin-engine

Me-262 "Swallow," was one of Reitsch's more routine rides. She also

tested a cockpit-equipped V-1 rocket and the insanely dangerous

rocket-powered Me-163 Komet. The Komet was powered by a binary fuel

that--when mixed together--exploded to provide thrust. Sometimes the

plane exploded, too, and, if that were not bad enough, the fuel provided

only five minutes of flight time, and the pilot had to glide home to a

landing. A second landing attempt was not an option.

One of the fuel components dissolves flesh, and sometimes there was

nothing to bury following a Komet fuel leak. The payoff was an aircraft

that could scream through an Allied bomber formation decimating it with

the impunity of a shark attacking a school of baby squid. The Komet is

the direct ancestor of many of today's most advanced delta-wing

warplanes.

The tragedy of Reitsch's remarkable life was that she chose to serve the

Nazis. When in State College, Pa., Reitsch proudly showed the owner of

the glider she flew a cyanide suicide capsule that was handed to her by

Hitler shortly before he killed himself in his dank bunker. Some

historians, blinded by her accomplishments, have tried to depict her as

a naïve, apolitical technician, but the fact that her parents committed

suicide rather than face life in a defeated Germany did not seem to faze

her.

Reitsch was a microcosm of a wartime Germany that was blessed with great

scientists and engineers like her colleague, rocket scientist Werner von

Braun. If the German fascists proved anything, it is that technological

advancement can proceed apace without parallel development in

humanitarian principles. It is very sad that Reitsch's remarkable

accomplishments will be forever tainted by the twisted cross that

adorned the aircraft that she flew so bravely.

In the very last days of

The Third Reich, she landed an aircraft on a shell-pocked street in

Berlin when most of the city had already been occupied by the Russians.

She spent two days in the "Fuhrerbunker" before returning to her

aircraft and taking off under a hail of heavy gunfire. Although her

politics were not popular in post war Europe, to say the least, she did

not hesitate to break the "glass ceiling" of women's aviation. In fact,

she smashed through it in the fastest and most advanced aircraft of her

day. Allied airmen were lucky that she was too valuable as a test pilot

to be risked on but a few combat missions

|